By Susan Martin, Senior Processing Archivist

You hear a lot of discussion nowadays about whether schools should still be teaching students to write in cursive. Less than half of U.S. states require it, usually sometime between third and fifth grade. I don’t know about writing cursive, but reading it is certainly a requirement for my job. And sometimes it’s especially challenging.

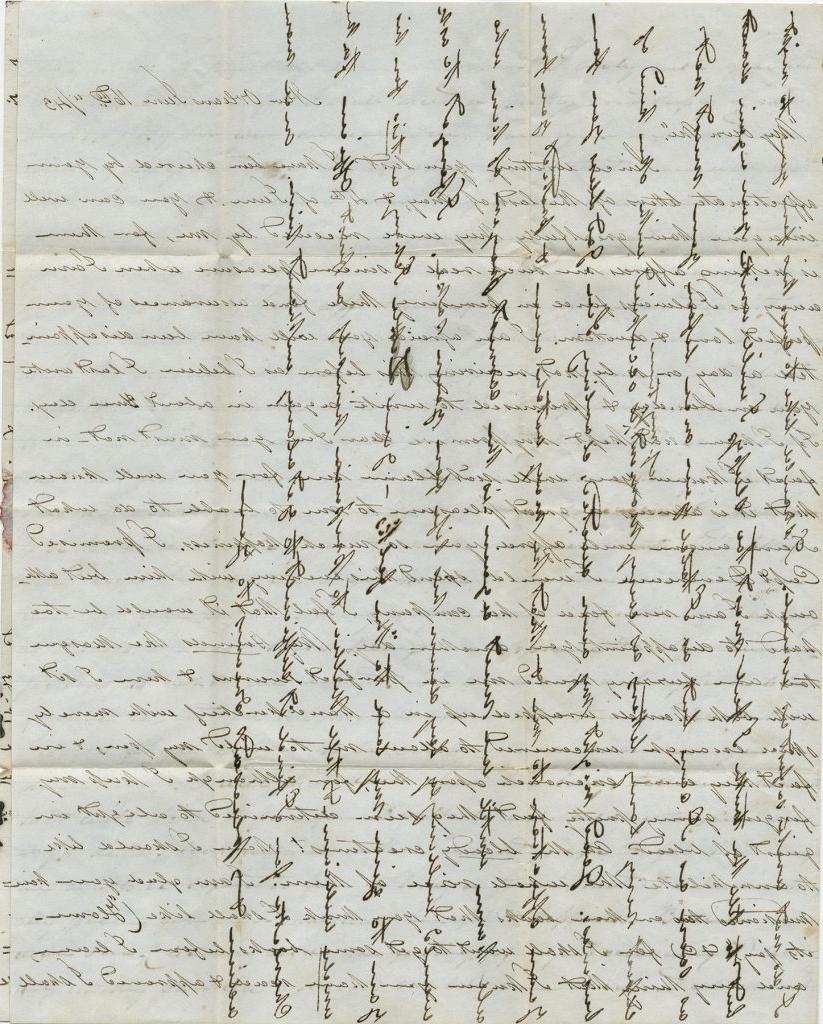

One of the things we see in almost every manuscript collection here at the MHS is cross-writing. Your garden-variety cross-written letter looks something like this.

This is the first page of a four-page letter, written on folded stationery. As you can see, the writer got to the end of the fourth page and had a little more to say, so went back to the front, turned the paper on its side, and finished the letter there. The idea was to save paper and postage.

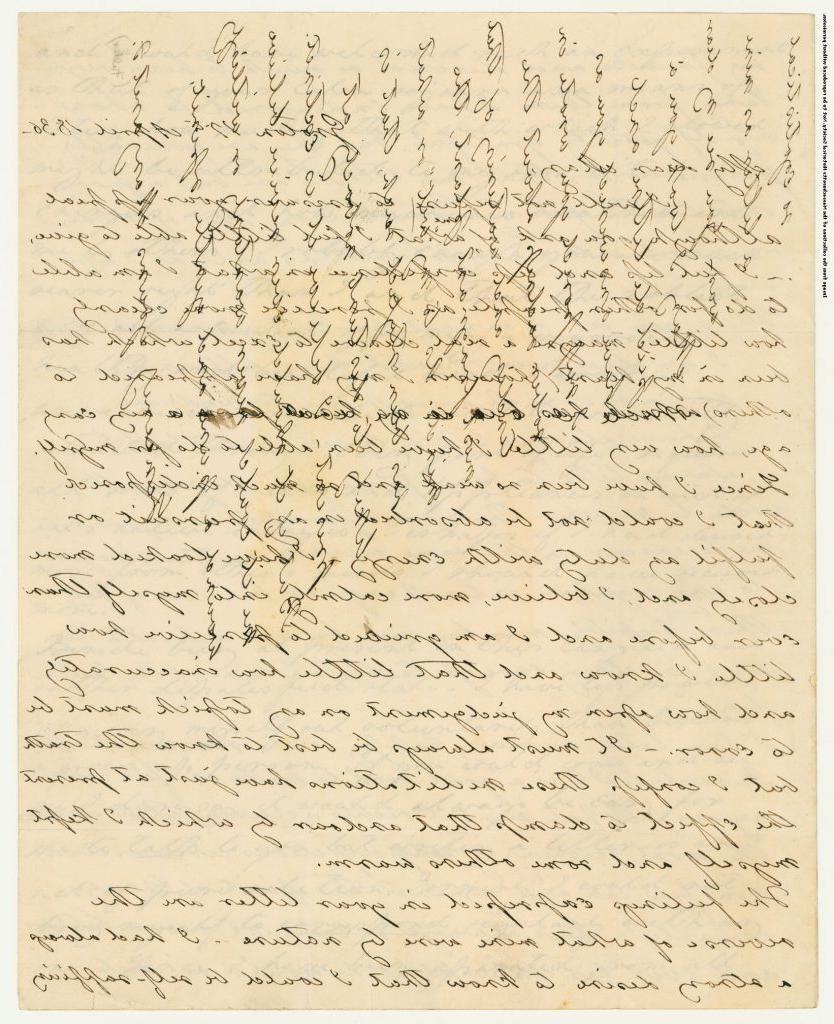

MHS archivists see pretty much every variety of cross-writing. The kind pictured above is very common. Here it is again in a letter from Margaret Fuller to Mary Peabody.

Letter writers have also been known to snake their writing around the margins of a letter or even to turn a written page upside down and write in the gaps between the lines. Sometimes they’ll change the color of their ink for the cross-written portion to make it easier for their correspondent to read.

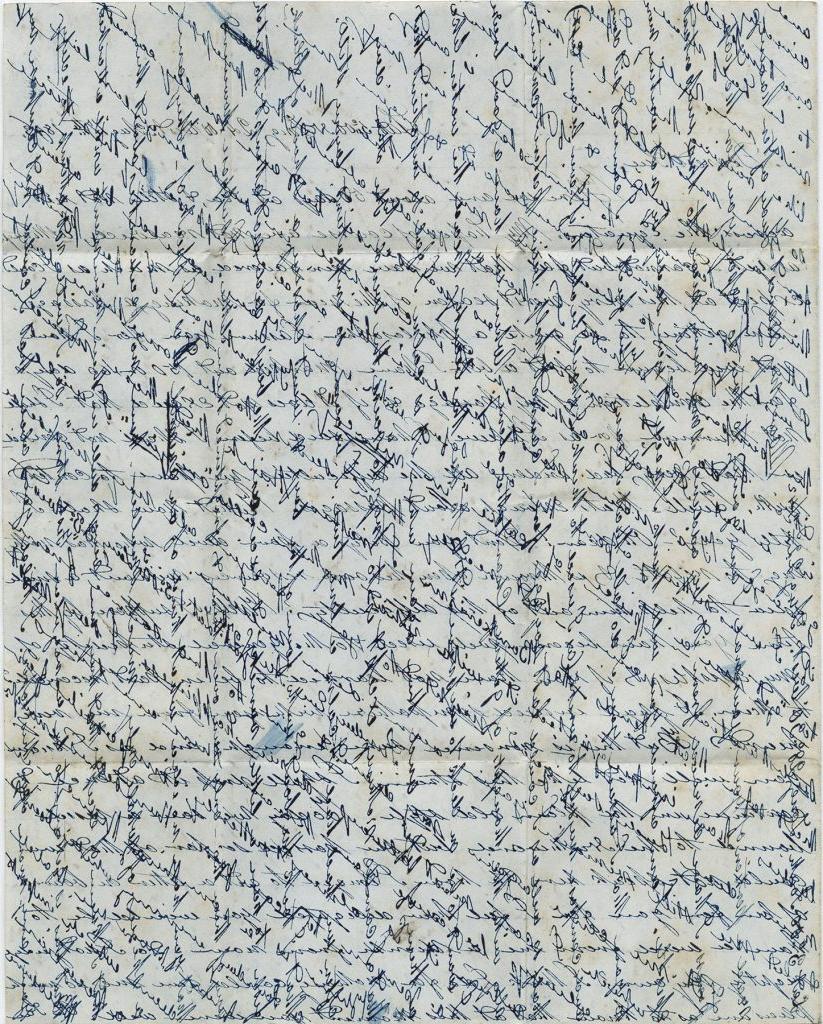

Then there’s this madness.

What you’re seeing here is a triple cross-written letter. It starts in the usual way, from top to bottom. The second pass goes from left to right, and the third is diagonal down the page. I don’t know about you, but trying to read this makes my eyes cross. With a lot of time and some fancy Photoshopping, I might be able to figure out what it says, but it would be tough!

This letter comes from the papers of William Blackler Gerry of Marblehead, Massachusetts. Gerry (pronounced “Gary”) was a master mariner in the China and India trade and commanded a number of ships, including the Charlotte, Beeside, Sappho, Farwell, Akbar, Cohota, and Noonday. The collection consists mostly of his correspondence with Mary Susan “Sue” Bartlett between 1841 and 1856, before and after their marriage. Included are letters written from Manila, Philippines; New Orleans; Liverpool, England; Pazhou (Whampoa) and Guangzhou (Canton), China; New York; Baltimore; Kolkata, India; Indonesia; and San Francisco.

If his surname sounds familiar, that’s because his grandfather’s brother was Elbridge Gerry, U.S. Founder, Congressman, governor, vice president, and inspiration for the word “gerrymander.”

William B. Gerry’s papers are chock full of cross-written letters. He even joked about it to Sue on 14 January 1843, when he wrote, “I fear your eyes will not like to behold a single letter now that you have been so used to those cross ones but I am afraid I shall have to close this without doing that for you.”

When it comes to reading handwriting, we all get better with practice. But every once in a while, something like this comes along to keep us from getting too confident.